An effective syllabus does more than let students know what to expect in a course; it may also provide a roadmap for navigating adversity, sustaining engagement, and accessing relevant supports. This tip-sheet is intended for course instructors who are interested to learn more about ways to support students’ academic resilience through syllabus design.

Defining the Syllabus

Your role as an instructor is central to student experience. While the classroom is the space where students show up to learn, the syllabus serves as a contract to guide that experience. Through the course syllabus, you not only communicate course expectations and policies (Harnish & Bridges, 2011), but also set the classroom’s tone. The syllabus is the first instance where you as the instructor can motivate learners to set goals that are high, yet achievable (Slattery et al., 2005)

When it comes to developing a syllabus, there are several essential components to include. While course syllabi vary widely in terms of format, length, and style, essential components include:

- Course description and details

- Required readings

- Link to relevant policies or learning supports

- A breakdown of course work and grading

- Key dates and deadlines

To learn more about these components, explore CTSI’s Developing a Course Syllabus guide.

Defining Academic Resilience

Academic resilience refers to “students’ capacity to perform highly despite a disadvantaged background.” (Ye et al. 2020, 176) A resilient leaner finds themselves able to meet and positively cope with stress and adversity and in doing so, enhance their flexibility and overall functioning. Individual experiences of resilience stem from the interaction of a person with their environment. As course instructors, we hold a power to shape the collective experiences of learners, so that the resulting processes promote well-being and growth.

Resilient learners do not face setbacks without tools to support them; academic resilience entails adversity, as well as experience of bouncing back through positive adaptation and the use of accessible resources (see Figure 1). Hence, a resilient learner learns from academic challenges, despite “environmental adversities brought about by early traits, conditions, and experiences” (Wang et al. 1994).

Figure 1 Resilience defined

In the following sections, we will explore syllabus design considerations that support three factors that are central to fostering academic resilience:

- Metacognition – the capacity to think about one’s own thinking; the process of planning, monitoring, and assessing one’s own learning.

- Self-efficacy – the personal belief in one’s capability to organize and execute effective action for academic engagement.

- Resourcefulness – the ability to problem-solve and find ways to overcome academic challenges.

While there are other factors connected to resilience, these three are especially relevant to our work in syllabus and assessment design. By intentionally designing our syllabus with these learner needs in mind, we may better support students’ abilities to persevere through challenges.

The electronic distribution of syllabi has made it so that viewing the course syllabus may likely take place before the first day of class, making it play a greater role in shaping how learners view the course and interact with faculty (Habanek, 2005; Harnish et al., 2011). When a syllabus is designed to foster academic resilience, it can more effectively build a constructive and supportive “course culture” that values:

- learning as a process that includes practice and failure

- learning as a collective experience

- the capacity to seek help before the moment of crisis

- the capacity to share, receive and apply feedback

Supporting Student Wellness though Syllabus Design

While a course instructor is not a mental health provider, their curriculum and course design choices can either help or hinder students to thrive. Discomforting emotions may often take place when learning, and these experiences can be positive forces, catalyzing new understandings and attitudinal change (Cutri and Whiting 2015). It is important that syllabus design decisions encourage students to take care of their wellness on their course journey, so that they can sustain their academic engagement.

Below are two strategies for syllabus structuration that supports student wellness. Read through them in any order, making sure to pause for self-reflection throughout.

Tip 1: Communicate positive messages about mental health supports

One consideration is to include a syllabus statement on mental health, to let students know that you are approachable and committed to sharing available resources to support their well-being.

Sample Syllabus Statement: Many students face personal and environmental challenges that can interfere with their academic success and well-being. If you are struggling with this class, please visit me during office hours or email me. If you are feeling overwhelmed and think you might benefit from additional support, please know that there are people who care and offices to support you at the University of Toronto. These services – including confidential resources – are provided by staff who are respectful of students’ diverse backgrounds. For an extensive list of well-being resources on campus, please go to: (link to your campus resource page)

In addition to offering a personalized message about mental health supports in your syllabus, you may want to allow one or more mental health days during the semester. A mental health day is when a student is allowed to miss a class, no questions asked, to support their own well-being. If a mental health day is something that you plan to offer, incorporating it into your syllabus statement on wellness would be an excellent idea.

When reviewing the course expectations and policies section of your syllabus, take a moment to consider these reflective questions:

- When sharing essential information (course description, learning outcomes, required readings), are mental health supports mentioned?

- In terms of tone, voice, and placement of elements, consider: Are you using supportive and inclusive language about mental health?

- In terms of length and design: are mental health supports mentioned early on?

- In terms of navigating how to use the syllabus: is the conversation around mental health normalized?

Tip 2: Mention mental health supports that are offered in and outside of campus

Navigating resources on campus is not an easy task, especially for a student who is new to the university atmosphere. Providing syllabus links to wellness-related resources can lower the barriers that a student may face in navigating resource.

If space one the syllabus is limited, one way to provide wellness resources is to link to an external shared document, where you have listed out a series of links that students may seek to access. To make this resource collaborative, you may consider putting the document in “editing mode,” so that students are able to suggest other resources that fellow students may find valuable.

Resource may be categorized according to themes that are meaningful to students, including:

- University wellness services

- Work from home strategies and resources

- Contemplation and mindfulness resources outside the University

- Relaxation and creativity resources

- Care support resources

Tip 3: Craft learning outcomes that emphasize the affective and emotional aspects of learning

As shared in CTSI’s Developing a Course Syllabus guide, learning outcomes describe the knowledge or skills students should acquire by the end of a particular assignment, class, course, or program. Traditionally, learning outcomes have served to help guide assessment and evaluation, and to support students to understand why the knowledge and skills being tested are useful for them.

By adding to your course learning outcomes an objective about the human dimension of learning, about our interdependence and interconnectedness, we support the building of empathy, respect, and care in the classroom.

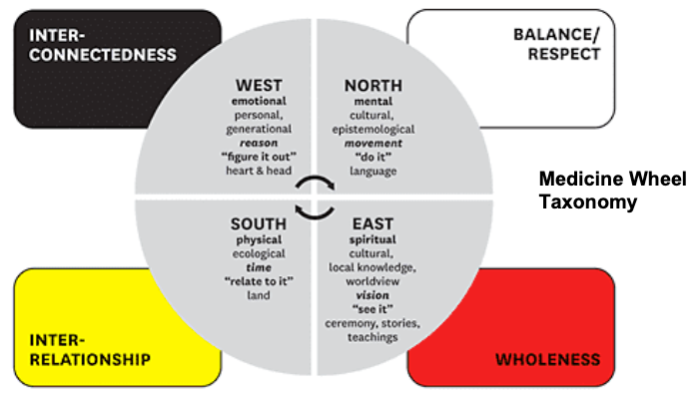

While it is not the only cultural framework available, the Medicine Wheel teaching/learning framework has widespread use in Indigenous communities, and is a valuable resource for course instructors (see Figure 2). The Medicine Wheel draws attention to four domains – Mind (mental); Body (physical); Spirit (spiritual); and Heart (emotional) – which can be used to guide the creation of learning outcomes in a way that serves all students, including the educational empowerment of Indigenous students. In this framework, we do not understand or interpret in just one of these domains, but move through them back and forth, in the listening and learning process. This movement aligns with how the Medicine Wheel acknowledges natural rhythms, in terms of how we move through the seasons, life stages, or the cycle of a day (Lafever 2017, 173).

Figure 2 The Medicine Wheel

In contrast to Bloom’s Taxonomy, which has three domains – Cognitive (mental), Psychomotor (physical), and Affective (emotional) – the Medicine Wheel holds space for the spiritual domain. While this is not the only cultural framework available, its emphasis on contemplation can serve as a useful resource for building empathy, respect, care, and wellness in the classroom.

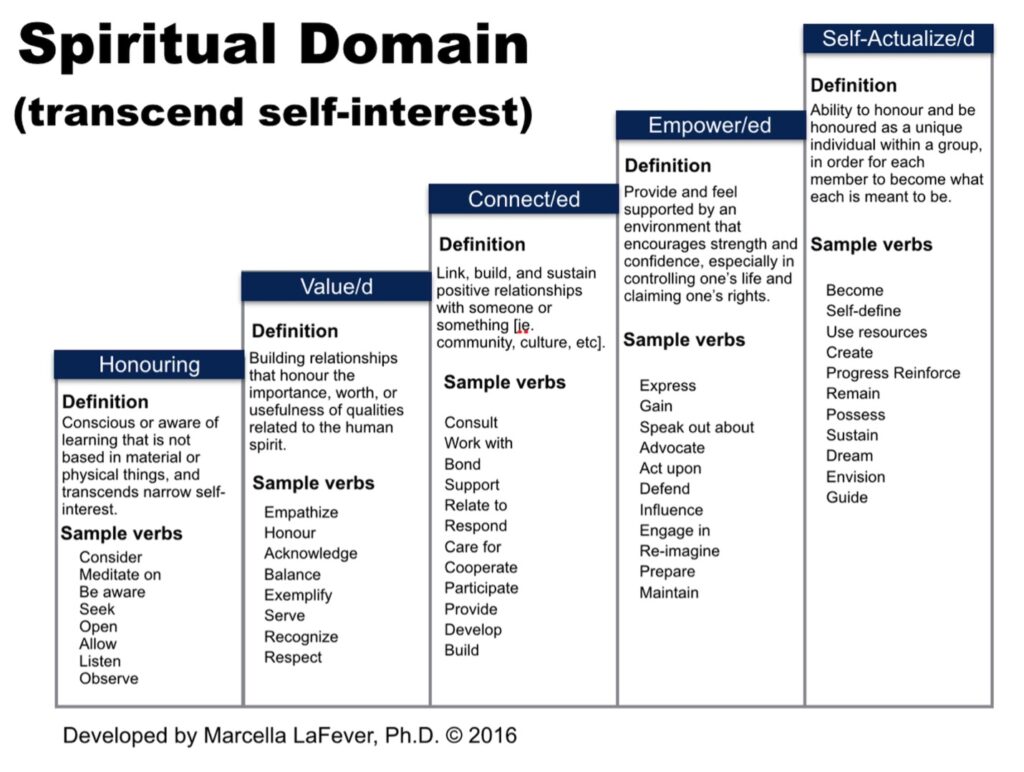

Marcella LaFever (2017) highlights five key learning outcomes that link to the Spiritual domain.

- Honouring (listening, self-awareness, and open-mindedness)

- Attention to relationships, transcendence of narrow self-interest

- Developing a sense of belonging

- Feeling empowered to pursue a unique path

- Developing self-knowledge of purpose

Figure 3 offers verbs and outcomes that can guide us to create learning outcomes that cultivate the Spiritual Domain of learning, as articulated in the Medicine Wheel. By intentionally imparting to your students that you want them to engage, to grow, and that there is responsibility that comes with knowledge, you support students to be resourceful, committed, and reflective—all key factors for building resilient learners.

Figure 3 Sample verbs and progression for creating outcome statement using the Medicine Wheel

Marcella LaFever (2017) offers a list of sample learning outcome statements that work across the progression found in the Medicine Wheel’s spiritual domain:

- Be aware of the emotional needs of other group members;

- Acknowledge that others’ feelings and desires are as important as your own;

- Work with group members to create an atmosphere that supports everyone’s input to a project;

- Advocate for group members when you see that they are not being heard;

- Remain committed to the completion of your group’s project.

Take a moment to consider:

What is one spiritual learning outcome statement that you could use to frame either your course syllabus, or a specific assignment?

Building Community and Promoting Participation in the Syllabus: Planning Ahead

A primary goal of resilient syllabus design is to maintain community and encourage participation, regardless of crises and interruptions to teaching that might arise. As stated in the previous section, promoting student resilience focuses on helping students through adversity. As instructors, we can create policies and statements in our syllabi that promote student resilience. Creating spaces for classroom community can be one way of motivating students to carry on with their learning in the face of adversity.

Three primary terms can help us consider how we might design our syllabus policies to maintain community and participation despite crises: preparedness, flexibility, and interactivity.

Resilient syllabus design asks that instructors think ahead to potential disruptions, and plan for them.

Here is a quote from U of T’s Policy on Academic Continuity that speaks to the need for preparedness in resilient pedagogy: The University “recognizes that events such as pandemic health emergencies, natural disasters, prolonged service interruptions, and ongoing labour disputes are potential threats to academic continuity.” U of T states that “Good stewardship requires that the University undertake appropriate planning and preparation to promote continuity.” Students can be adversely affected by all these potential interruptions. By designing your syllabus to promote resilience, you can help students to minimize these adverse effects, while maximizing academic continuity.

When planning your syllabus, think about potential policies you could include around health emergencies or inclement weather, so that students know what to expect and how the course delivery mode could shift depending on certain circumstances. Signposting these in advance is similar to the mental health policies/statements discussed in the previous section.

.

While preparedness is important to bring to course design, sometimes circumstances take us by surprise. In these situations, it’s crucial to remain flexible, responding quickly and effectively to new and sudden changes to the course. However, practicing preparedness ahead of crises can give instructors the space to remain flexible when crises do arise.

To ensure you remain flexible throughout teaching crises, you can begin designing your syllabus by identifying its learning outcomes (either course-wide learning outcomes, or week-to-week learning goals). Once you have those goals explicitly stated, you can respond to course changes or teaching crises with an eye toward preserving those learning outcomes. You might ask: How can I maintain my course’s/lecture’s learning outcomes with a shift from in-person to online learning? How can I maintain content continuity if I must cancel a planned lecture? How can I adequately assess students based on these learning outcomes if I need to switch from an in-person test to a take-home exam?

Include these learning outcomes on the syllabus, alongside your policies and statements on potential disruptions to learning (inclement weather, illness, etc.). This can set expectations for students, minimizing their anxiety, while demonstrating that the course will incorporate flexibility into its teaching methods.

The final term that can help us consider how we might use resilient syllabus design to preserve community and promote participation is interactivity. As instructors, we consider the different forms of interaction that take place in the classroom, plan for these interactions (exercising preparedness), while simultaneously planning alternative modes of promoting these forms of interactivity if a crisis should occur (exercising flexibility).

Bill Hart-Davidson, in his essay “Imagining a Resilient Pedagogy,” identifies interactivity as a key component in post-pandemic teaching. Rather than focusing on the communication of course content, a resilient pedagogy also focuses on how students interact with you as the educator, with each other, and with the asynchronous course content. Our goal with resilient pedagogy is to maximize interactivity while minimizing disruption.

Let’s look at another quote from Hart-Davidson: “A resilient pedagogy requires planning for the important interactions that facilitate learning. These include all the ways that teachers and students need to communicate with one another, see one another, learn from one another, in a variety of contexts that are important to our learning goals and outcomes. It also includes the way students need to see, shift their perspectives of, manipulate, and practice with the objects that scaffold their learning.”

In other words, we must focus on how the various components of classroom learning – students, teachers, course materials, tech – interact with each other, and how certain interactions might facilitate more effective learning than others in each context. This, again, requires examining your tutorial’s learning goals and identifying best practices for reaching those through interactivity.

We can consider interactivity by breaking down classroom interactions into four primary interactions: student-student, student-teacher, student-content, and student-technology.

By sharing details on how interactivity will take place in the syllabus, students are more likely to feel better prepared for the course with clear expectations and a sense of feeling ready to learn from academic challenges. For instance, you might include a “Participation” section on the syllabus, outlining all the ways students can garner participation marks across course-based interactions (e.g., speaking in class, small-group or pairs work, attending office hours, etc.).

You can even highlight potential exercises you will undertake in class, to set clear expectations for students as to their interactions with course materials and other students in (and outside of) class.

When designing your syllabus, you can include partial lists like these (below), that speak to forms of interactions you might expect of your students:

Some expectations for student-student interactivity in in-person classrooms include:

- Think-Pair-Share exercises

- Group work (responding to questions, filling in worksheets)

- Group brainstorming sessions

- Peer editing

- Lab work in pairs

Some expectations for student-teacher interactivity in in-person classrooms include:

- Discussion questions in lectures

- Office hours (you can even assign participation marks for attending office hours)

- Surveys and feedback forms

- Assignment feedback

Some expectations for student-content interactivity in in-person classrooms include:

- Independent reflection activities (e.g., responding to a question about a reading)

- Knowledge Check-Ins in class (multiple choice questions, Q&A, etc.)

- Short Quercus quizzes to check for content comprehension

- Essays, oral presentations and other long-form assignments

Some expectations for student-technology interactivity include:

- Quercus tour videos

- Online Discussion Boards

- Quercus quizzes

- In-class WordClouds (via Mentimeter) or anonymous posts (via Padlet)

- Shared WordDoc

Alongside these lists, you can also include a policy statement speaking to your expectations of students in class.

For instance: In this course, students will be expected and encouraged to engage with their peers and the course materials in several key ways: in class, through small group discussions and activities; online, through Quercus Discussion Boards; and in office hours, in one-on-one meetings with me. These multiple modes of participation exist to help you through any potential disruptions you might experience over the course of a semester. For instance, if you have disrupted travel plans and cannot make it back to Toronto for one week, you can still gain participation marks by posting on the Discussion Board.

By exercising preparedness, flexibility, and interactivity, course instructors can ensure that community-building won’t be disrupted, even amid crises.

Before moving on…consider the syllabus you’re designing now, or a syllabus you would like to design, and reflect on the following:

- What are my syllabus’s leaning goals/outcomes?

- How might I exercise preparedness, flexibility, and interactivity to meet these learning goals if a crisis should occur (e.g., inclement weather, health crises, etc.)?

- What strategies can I deploy to promote participation through these different modes of interactivity (i.e., student-student, student-teacher, student-content, and/or student-technology)? How might I write a policy statement on participation?

Building Community and Promoting Participation: EdTech and Interactivity

In recent years, many disruptions to teaching have resulted from sudden shifts from in-person to online teaching, or vice versa.

By planning for various course delivery changes, we can maintain interactivity, community, and participation. Educational Technologies (EdTech) are great tools and resources to turn to when shifting a course’s delivery method.

To determine which EdTech tools are best suited for your course, you can reflect on the following questions:

- How can I maximize interactivity between students/myself online and in-person?

- What forms of interactions are the most effective for teaching my subject matter?

- Which EdTech tools do I already have access to? Which am I already familiar with? Which tools would I like to familiarize myself with?

- What are some pros and cons of each EdTech tool I’m considering working with?

- How can I make participating in the course as accessible as possible without exceeding my labour hours?

You can check out U of T’s EdTech Guide for information on university approved EdTech tools.

By preparing your EdTech tools in advance, comparing them, and thinking about their impact on course interactivity and participation, you can ensure that participation remains consistent across potential course disruptions.

Let’s look at some commonly used EdTech tools and think about how they might be used to promote interactivity, fulfilling the goals of resilient course design.

Quercus course websites can, first and foremost, be used as communication tools to provide important updates and announcements for students. On your course syllabus, and in the first week of class, you can highlight for students the importance of having their Quercus notifications turned on, so that they don’t miss important updates.

- e.g., If you need to move a class online due to inclement weather, you can let students know via the Announcements or Inbox features

Quercus can also be used an alternative, asynchronous method of grading participation.

- You might post a public, open Discussion Board on Quercus, where students can gain additional participation marks by asking questions, responding to each other, etc.

- You can also open ungraded Quercus submission portals for participation responses.

Reflection Exercise: Think about the two uses of Quercus suggested above (the public Discussion Board and the Quercus submission portal). What are the pros and cons of each strategy for grading participation? How does each strategy meet the learning outcomes of your own course?

- These forms and surveys can be used to foster student-teacher interactivity and offer space for alternative participation marks.

- For instance, an instructor might leave open a Microsoft Form all semester that asks students to submit questions they have about the material. You might use those questions to structure your lectures, thereby incorporating student feedback and student-directed learning into your teaching. These questions could be anonymous or count as participation marks.

- Opening a SharedDoc in OneDrive or SharePoint can be great for promoting participation via group work and/or promoting nonverbal participation.

- For instance, you might separate students into groups, asking them to reflect on a discussion question. The group would then assign a scribe, who would input their responses into a table or feedback form on this SharedDoc.

- You can also use SharedDocs for independent reflection activities.

- SharedDocs thus promote interactivity and community in an online or in-person setting.

Exploring these various tools can be instrumental for sudden shifts in course delivery method. As we’ve covered in the previous section, flexibility is hugely important for resilient course design. When working with EdTech tools, you can develop charts that compare and contrast how various activities could be undertaken in-person vs. online.

With these strategies and resources under our belts, let’s consider a Case Study:

You teach a course that has a weekly lecture/discussion. You are the sole Course Instructor and point of contact for all students. It is a 300-level course, with no additional teaching or grading TAs. You realize the day before your next lecture that a snowstorm is moving into the city, and an Extreme Weather Warning is in effect, warning against unnecessary travel. This week’s lecture is integral to the course’s narrative, and you’d been planning to undertake a small-group assignment in class that would ask students, in groups, to closely read and analyze a key quote from the readings, before relating it back to a contemporary event in the news. You had been planning on these groups writing their thoughts down manually on paper, and handing them in at the end of class for participation marks. With the incoming inclement weather, you decide to move the class to Zoom.

How would you adjust this course to an online setting? How would you communicate these adjustments to your students? Which EdTech tools might you use to facilitate interactivity amid a switch to an online setting?

Clarifying the Course Journey through the Syllabus

When designed with a focus on transparency and incremental process, the syllabus can serve as a clear guide for students, letting them know what the step-by-step journey of the course looks like. Not only can this support students who may feel overwhelmed by challenging course material, it can serve as a key learning tool; rather than think about the course in a large, abstract sense, students are invited to examine how the weekly lectures or seminars are all smaller pieces of a larger whole. This kind of analytic thinking may generate curiosity, as well as metacognition about their learning experience.

Below are four strategies for syllabus structuration that support student resilience. Read through them in any order, making sure to pause for self-reflection throughout.

Tip 1: Map out the narrative arc of the course

The syllabus tells a story. The sequencing of the weeks’ readings links to the learning outcomes and has a beginning, middle, and end. While learning outcomes are key features of a syllabus, even before that, it is critical for us as instructors to have an overall objective for the course. What key learnings do you want students to take with them? Once we understand why we believe the topic matters for your students, and what techniques—tools, methods, and terminologies—that you want them to learn, you can consider how you want to convey that information through the readings, assessments, and in-class work. In addition, that information can be effectively conveyed through the way in which you structure and thematize the process of moving through each week’s readings and lectures.

Some strategies for making the course architecture of a course as clear as possible include:

When thinking about the beginning, start at the end. Where do you want your students to be at the end of the semester? Start with the key learnings that you want to teach to students, and then, using backwards design, consider how you can break down the weekly classes into 3-4 (or more) modules or thematic topics.

Once you have a clear idea of the key themes or modules, map out the weekly reading list in a way that creates links between one class and the next. In doing this, you are letting students know that everything ties together and has a purpose. Dividing the weeks into 2-3 units can additionally help to shape the story that the syllabus is telling.

To map out connections across the weeks, consider offering a short description of what concepts or themes each particular week will explore.

To support students’ metacognitive engagement, consider including a guiding question for specific weeks or sections, to encourage students to reflect on that question while preparing for class. This can help students to develop a sense of knowing of where they are going, along with a sense of anticipation and excitement around what they will learn going forward.

Before moving on… Find a syllabus from a course you’ve previously taught, and/or from a course you’ve recently taken. Take a moment to look over the weekly reading list, especially in terms of how it is structured and framed. Ask yourself:

- Is it clear why the reading list is structured in this sequence?

- Does there appear to be an overall arc or story guiding the progress of each week’s readings?

Tip 2: Apply learner-centered language that highlights your values as an instructor

While traditional syllabi often focus on course content, it is valuable to structure a syllabus around the student learning experience. For instance, when we shift the language of your syllabus from “what the course will teach” to “what the student can learn,” we invite learners to identify as unique agents of learning, engagement, and connection. This supports all students, including those who have been historically underrepresented in university settings.

Some strategies for prioritizing learner-centered language are:

- Rather than state “this course will…” or “students will…”, consider writing “we will…” and “you will…” When students read this, they are invited to conceptualize themselves as part of a bigger team, which they are free to commit their energy and time to.

- Consider sharing a self-introduction as the instructor, as well as your approach to teaching. This emphasizes pedagogical transparency and approachability.

- Explicitly state how you will provide opportunities for feedback and shared governance in the course. This may look like highlighting community agreements or anonymous feedback forms, for instance, in order to support an inclusive class atmosphere, where learners have space to share their reflections and needs.

- Considering integrating your commitments as expressed in land acknowledgements and other policy statements into the syllabus, so that students are introduced into the course with a sense of the key values of the course.

Example self-introduction:

“I approach teaching this course with the firm belief that all students can learn well and succeed, and my focus is on providing you with the materials, activities, and supports needed for you to do so. The readings and activities in this course can be challenging, but I am striving to make this course a collaborative environment in which we work together to learn with and from each other, and there will be plenty of opportunities for help and advice from peers and from the teaching team. Please reach out to us during office hours or via email. We are here to help you succeed!”

Before moving on… Find a syllabus from a course you’ve previously taught, and/or from a course you’ve recently taken. Ask yourself:

- How might you meaningfully acknowledge the Indigenous lands on which the course takes place, whether in person or online?

- What foundational beliefs and values drive your approach to teaching, and underlie the course design?

How can sharing with learners the rationale for the course design and teaching methods help them to better engage and learn?

Tip 3: Break down the process of accessing resources

It is critical that students are easily able to locate and access relevant course resources, such as session notes, lecture slides and recordings, and readings. While traditional syllabi may not consistently map out where these resources are found, these details are now important tools for maximizing student success. This is especially the case since COVID-19, when the tools used for delivering courses has expanded what kind of course resources exist. As instructors, it is our role to clarify the resource-retrieval process, so that students generate the resourcefulness necessary to become resilient learners.

Some strategies for breaking down the process of accessing resources are:

Be intentional and clearly communicate design choices about if, and how, learners will be able to access course resources. This can help build understanding for the structure and flow of your course as well as lower the metacognitive load around locating and accessing materials.

Provide a “how to” for accessing course material, including slides, lecture notes, or online modules. By including contextual information and direct links to accessing course resources, learners will be less likely to experience frustration and barriers to learning. In addition, consider being explicit in stating which materials will be used in each week or session.

If there are both optional and required readings, consider being explicit in mapping out which texts belong to which category. If the readings are available at a specific website or library, providing specific details on that information will ensure that students has immediate access to the material that they need to succeed in their learning.

This can involve including information about whether learners should focus their attention, or what strategies they should use to learn best from the materials. If lecture videos are recorded, for instance, it is helpful to let learners know whether and how they should review them. One option for providing resources on reading can be to provide a “how to read in the discipline tip sheet.” Whether you make your own tip sheet or provide a link to a relevant external resource, this act will invite learners to use relevant tools that support their learning.

Example: How to best learn from these materials:

“You will be able to master the topics in the course and do well if you attend class, work on the problem sets, and do the readings. Previous learners have suggested that the most effective strategy for this course is to read the associated chapters/pages for the textbook before the corresponding class. That way, you’ll be familiar with the topics before the class discussion and activities. After class, or before exams, it can be helpful to review class notes and do the practice questions. Please do not spend too much time on rewatching the videos, as reviewing the notes and working on the practice questions is a more effective use of your time.”

Before moving on… Find a syllabus from a course you’ve previously taught, and/or from a course you’ve recently taken. Ask yourself whether it is clear…

- Why the textbook and other course readings have been selected for the course and what are the options for learners to access them?

- Is any guidance provided on how learners can best learn from the course materials?

- Is it clear how much time learners should anticipate needing to complete any assigned readings?

Tip 4: Incentivize students to actively read the syllabus

Once the syllabus is ready, the next step is for us to consider how we can motivate students to see the syllabus—rather than you—as their starting point for information about the course. Whether the course is in-person or online, there are a number of techniques we can engage to support students to search out information in the syllabus.

Some strategies for engaging students with the syllabus include:

- Consider creating an email signature that clearly guides students back to the syllabus, including a URL link for accessing the document.

- Consider creating a Syllabus Tour Video, and placing it on the Quercus homepage, to offer students and accessible and engaging way to learn about the syllabus components.

- Within the first week of class, consider creating an activity around exploring the syllabus, especially the parts that are less related to evaluation; research suggests that students pay most attention to sections of the syllabus that detail information on assignments and due dates.

- Activities could include:

- Learning outcome mapping.Assign one of the course learning outcomes to groups of two to four students. Each group must map how that particular learning outcome relates to the course content and course evaluation components.

- “Figure out why” activity.Have students review the class policies in small groups. For each policy, ask the students to discuss why they think the policy exists. Follow this with a class discussion about the rationale for the class policies.

- Syllabus quiz.Hand out a quiz with 10 true or false or fill-in-the-blank questions that can be answered with information in the class syllabus. Have groups of students work together to complete the quiz. Review the answers with the full class, inviting any questions for clarification.

- FAQ search.Create a list of frequently asked questions that you have received in the past. Have students work in pairs to find the answers in the syllabus.

- Personal assessment.Provide students with a feedback sheet on the syllabus that asks them to connect personally with it. For example: Which of the course learning outcomes interests you the most, and why? Which of the course assignments do you think will be the most challenge to you, and why? (Questions adapted from Linda Nilson, Teaching at Its Best, 2010, 40-41.)

Before moving on… Find a syllabus from a course you’ve previously taught, and/or from a course you’ve recently taken. Ask yourself:

- What concerns do you think that students would find with understanding the material?

- What syllabus-engagement activity would be useful to invite students to engage in, to support their understanding about those concerns?

Techniques for Assessments and Feedback

When designing assessments with resilient pedagogical practices, a tension arises: How might we support student resilience while simultaneously assigning grades to and providing feedback on their work?

To resolve this tension, practitioners of resilient pedagogy should remain mindful of techniques and strategies for equitable assessments. With the right planning and tools at hand, it is very much possible for instructors to practice resilient pedagogy through assignment design and assessment feedback. You can also use your syllabus to signal to students why and how these assessments promote their own learning, and encourage resiliency.

Below are five strategies for assessments that practice resilient pedagogy. Read through them in any order, making sure to pause for self-reflection throughout.

It is important to develop clear learning objectives for each assignment; when students can understand why they are being asked to develop a certain assignment, they will be more effective at linking course concepts and ideas to that assignment. This can help make assignments feel less overwhelming to students, supporting their resilience as they navigate difficult semesters balancing work, home, social, familial, financial and/or educational responsibilities.

Some strategies for increasing assignment clarity are:

- Deploy active and descriptive terms (adjectives and verbs) in your assignment description

- For instance, instead of writing, “Write 5 pages on x topic,” you might write, “Write a 5-page research paper on the implications of x topic for the field of y,” or “Write an annotated bibliography on x topic in preparation for your final paper,” or “Develop a 10-minute oral presentation on the history of x, as it relates to Unit I of the course,” etc.

- Situate the assignment within the larger scope of your course

- You might begin an assignment description with a brief contextualization, such as: “In Unit I of this course, we covered Canadian women’s literature of the 1960s and ‘70s, and its themes of intergenerational relationality, the domestic, rural life, and the pressures of motherhood. Your Unit I paper should address these concerns by mounting an argument for the relationship between gender and space in one novel covered in class…”

- Describe the learning objectives of this assignment. What do you hope students will learn/take away from completing this assignment?

- Outline integral components of the assignment

- For instance:

- Specify whether a written paper must have a thesis

- Explain whether an exam can be written in point-form, or must be in complete sentences

- Clarify which citation style is mandatory, how many source

- Develop a rubric explaining your expectations for an A-, B-, C-, and D-level submission, using clear, active, and descriptive language

- Include sample papers, if possible, at both an A and B level

- Address the assignment in class

- Give yourself time at the start or end of a lecture/discussion period to address any questions or concerns students might have about the assignment

- For instance:

For more information on assignment clarity, visit the TATP’s Toolkit Resource, “Writing Assignments,” Queens University’s module, “Making Assessment Criteria Clear to Students,” and Conestoga College’s article on “Creating Clarity in Assignment Descriptions.

Before moving on… Find an assignment description and/or rubric from a course you’ve previously taught, and/or from a course you’ve recently taken. Circle any language that seems vague or unclear to you. Underline language that seems clear and specific. How might you improve this assignment description and/or rubric to make it clearer for students? What are the learning objectives set out here? What questions could you anticipate a student asking about this assignment?

Scaffolding is another key technique for supporting student resilience. Scaffolding assignments entails breaking down learning outcomes and assessment expectations into manageable bits. It can also be referred to as chunking.

For instance, if you’re assigning a Final Research Paper for your course, you might break that down into multiple, smaller assignment submissions, such as: an Annotated Bibliography, Final Paper Proposal, and/or Thesis Statement Exercise. If your final assignment for your course is a Final Exam, you might scaffold that assignment around Weekly Online Quizzes, a Midterm Exam, and/or Reading Responses.

Scaffolding allows you to ensure that students are not falling behind on course materials. It also allows you, as the instructor, to identify and aid students who do seem to be struggling with course materials, before they hand in a heavily weighted final assignment that will greatly affect their final grades.

Scaffolding also incorporates processual feedback into the assignment submission process. For instance, if you assign a Final Paper Proposal ahead of a Final Paper deadline, students will be sure to receive feedback on their initial ideas, arguments, and sources; they can then incorporate that feedback into their Final Paper submission. For this reason, scaffolding can often facilitate greater improvements for students.

For more on scaffolding assignments, see TATP’s Toolkit Resource, “Scaffolding and Student Supports.”

In other words, feedback is crucial to scaffolding assignments. Providing effective feedback over multiple steps of a student’s journey from initial ideas to final draft promotes student resiliency by highlighting process and improvement over mastery.

But how do we promote student resiliency through written feedback? Read on to consider a few ways that written feedback can actually support resiliency in student learning.

As previously mentioned in this resource, the idea of providing written feedback and grades on student assignments seems at odds with resilient pedagogy. However, by reflecting on how and why you give written feedback to students can create feedback styles that support, rather than compromise, resilience.

Pause here, and ask yourself: Why do I give students feedback? What am I hoping they learn from my feedback?

Some common answers might be: to help them improve their grades in the future; to encourage them to continue developing certain skills (critical reasoning, rhetoric, writing with personal voice, analysis, etc.); to highlight areas for improvement; and to motivate students to reflect on their own learning processes.

All these reasons are in support of resilient pedagogy. We provide feedback so that students understand how to improve on certain skills, and so that students understand that everyone has room for improvement. We also provide written feedback to teach students how to receive critiques.

However, it is important to structure the form and style of our feedback, so that students understand that: a) feedback is not a personal attack; b) instructors want to see their students succeed; and c) feedback is not meant to paralyze or halt their progress, but motivate and support it.

To develop these effective feedback structures, you can use the following strategies:

- Explain clearly and concisely why the student received the grade they did

- If a student sees “Good job!” or “This could be better,” in their assignment feedback without much contextualization of explanation, it might leave them unsure of how they can improve. Make sure to explain why the student received a high or low grade.

- Offer suggestions for revisions

- Instead of marking moments that “don’t work” in a student exam or essay, you can highlight strategies for improvement. For instance, instead of writing “this thesis is unsupported,” you might write, “This thesis could use additional quotes or citations from x and y sources to bolster its claims.”

- Highlight campus resources for assignment help as next steps

- Sometimes, course instructors cannot follow a student’s progress as closely as they would like to, given contract limitations. If a student is struggling with course materials, and that struggle is reflected in their grades, you can include resources in your assignment feedback that might help them improve. For instance, if a student is really struggling to structure their essays, you might direct them to a Writing Centre. If a student is having trouble finding appropriate scholarly sources, you might direct them to a University of Toronto Library or the Ask a Librarian chat service.

- Focus on the work, not the student

- When providing written feedback, make sure not to use personal language. For instance, instead of saying, “Your argument feels unsupported at times,” you can write, “This essay’s argument could be better supported.” This helps to separate the student from their work, subtly reminding them that personal feedback is not a personal attack, and that their personal value is not represented by their grades.

- Think of yourself as a coach

- Just as the coach of a sports team uses a mix of constructive criticism and positive reinforcement to hone their players’ skills and confidence, you should think of your written feedback as a way of boosting students’ motivations to improve. Even if a student has not completed an assignment successfully, resulting in a lower grade, try to frame your feedback as coming from someone who is rooting for that student.

Read the following feedback comments and reflect on how they do or do not promote student resilience:

- “Too vague!”

- “This assignment demonstrates a sincere engagement with the text—I really enjoyed reading it! I do think the thesis statement here could be better supported, using 1-2 more sources/more quotations and citations to bolster its claims.”

- “I can tell you wrote this in 15 minutes.”

- “Very nice!”

- “This submission is a huge improvement from the final paper proposal. I’m delighted to see it! It’s clear that my previous feedback was taken seriously and incorporated into this final draft. This essay reads clearly and argumentatively, uses appropriate sources throughout to bolster its claims, and is logically structured to flow from one key idea to the next.”

For more on providing feedback, see TATP’s Toolkit Resource, “Giving Feedback on Written Work” and the University of British Columbia’s presentation, “Providing Effective Feedback on Writing Assignments.”

In resilient syllabus design, you can include an “Assessment Feedback” statement that explains your approach to grading, to set clear expectations for students. An example might be:

This course focuses on written essay assignments. We will be scaffolding from short reading responses up to a final, engaged research essay. In my feedback across the semester, I will be looking for: a) an ability to take and apply my own feedback, demonstrating a desire to improve; b) unique perspectives and arguments; c) a sincere effort to support argumentation with clear, well-researched, appropriate evidence; and d) a personal voice. Please see the detailed rubrics on each Quercus assignment submission portal for more details.

Resilient pedagogy can be practiced by encouraging students to reflect on and develop their own models of (self-)assessment. This can take the form of asking students to reflect on their performance on recent essays, exams, etc. with worksheets called “assignment wrappers.” For more on assignment wrappers, visit Carnegie Mellon University’s “Exam Wrappers” page.

In this resource, we are going to think about how self-assessment can be used to promote participation, a mode of assessment that often requires student resilience. Due to a global pandemic, increasing mental health concerns, and rising costs of living, students in recent years have struggled to attend and participate in class. How might we, as instructors, promote resilience by encouraging and motivating participation?

Here are some strategies for using self-assessment to promote participation:

- Co-Creation of Participation Criteria:

- At the start of the semester, you can have a roundtable discussion with your students (or send out a survey) about potential issues around attending class. This is not to say that participation in class should not be taken seriously. Rather, this provides an opportunity for the students to come together and mutually decide on fair and equitable expectations around participation. This can also highlight any barriers to access/participation that some students might be experiencing, allowing you to reflect on alternative modes of participation.

- For instance, you might ask your students the following questions, collect their responses, and then develop a participation rubric based on their time constraints:

- How many classes per semester do you feel are fair to miss? What is the limit of missed classes without receiving a penalty?

- How many classes per semester do you feel should be attended to receive an A grade in participation?

- Are there types of participation assessments you would like to see in this course, aside from in-class verbal contributions? (e.g., written responses on Quercus, office hour visits, small group work in class, etc.)

- Are there any forms of participation you feel are not accessible to you?

- If you miss a class, how do you feel is a fair way to make up that participation mark?

- Self-Assessment Reports

- At the midpoint of your course, you can send out a survey to all students, asking them to reflect on what they think their current participation mark should be, based on their contributions thus far.

- Some questions you can consider asking are:

- I had read all the assigned works carefully before I came. (Yes/No, feel free to expand)

- Out of all the class seminars so far, I attended _____sessions.

- Did you contribute to class discussion each class? If so, how many times did you generally contribute?

- My goal was to contribute effectively to the high quality of the groups discussion and learning rather than just to demonstrate my own excellence. As in team sports, I played for the well-being of the team. (Yes/No, feel free to expand)

- Source: ANT441 Student Self-Report on Class Participation

The goal here is not to allow students excuses not to participate. Rather, by asking students to self-reflect on their own levels of participation, and ideas of fairness and equity around participation, instructors motivate students to engage in self-directed learning, take seriously questions of academic integrity, and reclaim ownership over their own path through higher education.

Research shows that, often, students are harsher toward themselves than their instructors, demonstrating that self-assessments can provide moments for instructors to discuss pressures of perfectionism placed on students today.

In short, developing participation assessment criteria through student self-assessments and class co-creations of rubrics, guidelines, etc. builds classroom community and generates a sense of responsibility among students for their own success. This can build resilience by showing students that:

- a) Participation criteria do not have to be opaque;

- b) Participation grades can be improved even after the midpoint of a semester; and

- c) Participation in class can be achieved in a variety of ways (verbal contributions, office hour visits, written responses, etc.).

For more on self-assessments, visit Cornell University’s article on “Self-Assessment” techniques.

Our final strategy here for supporting student resilience via assessments is to institute flexibility around late marks.

Over the past few years, professors and CIs have noticed an increasing demand for extensions from students. Some instructors have opted to do away with deadlines altogether, only to find that this led to student opt-out and disengagement.

However, using flexibility within structure to develop late mark policies in your course can be a way to avoid student burnout and mental health issues, while ensuring they stay engaged with and on track to complete the course.

Here are a few strategies for instituting late marks that take on this flexibility within structure concept. You can include any of these policies on your syllabus, to again promote resiliency through pedagogical transparency:

- Grace Periods: You might consider instituting a grace period of 48-72 hours after an assignment deadline. Students can submit during this period without having to email you for an extension, thereby reducing your own administrative labour, while ensuring students can take a bit more time if necessary.

- Rolling Deadlines: You can have students decide their own deadlines, based on their own schedules. Students can sign up using a collaborative calendar, so that they don’t need to email you directly. You can institute these rolling deadlines within a certain period (e.g., Paper #1 can be due between February 1st and February 14th). That way, you can still plan your grading around these self-imposed deadlines.

- Maximum Late Penalties: You can signal to students that their late penalties will not rise above a certain percentage. For instance, you might tell them that you will not take off more than 10% of their grade. This clarifies expectations, and lets students know that their grade will not be hugely affected, incentivizing them to finish the assignment.

- Extension Deadlines: Let students know that if they ask for an extension at least one week before a deadline, you will grant it immediately. This motivates students to reflect on their time management well ahead of a deadline, and consider what extra supports they might need.

It is often more satisfying for an instructor to accept a late, well-written and well-researched paper than an on-time, rushed, and unsuccessful paper. When considering your late mark policies, try to remember that students are navigating a lot of overwhelming, competing demands on their time. Instituting grace periods, rolling deadlines, maximum late penalties, and/or extension deadlines can be a great way to support student resilience while maintaining the integrity of student assessments.

For more on Techniques for Assessments, see the TATP’s Toolkit Resources on “Assessments.”

All these techniques listed above help build relationships and trust with your students, encouraging them to work through adversities and setbacks and motivating them to complete their course successfully. Student resiliency can be promoted through assessment and syllabus design, rather than in spite of it.

Sources Consulted

- Harnish, R.J., Bridges, K.R. Effect of syllabus tone: students’ perceptions of instructor and course. Soc Psychol Educ 14, 319–330 (2011). h

- Slattery, J. M., & Carlson, J. F. (2005). Preparing an effective syllabus. College Teaching, 53(4), 159–164.

- University of Toronto, “Developing a Course Syllabus”: https://teaching.utoronto.ca/resources/developing-a-course-syllabus/

- Habanek, D. V. (2005). An Examination of the Integrity of the Syllabus. College Teaching, 53(2), 62–64.

- Harnish, Richard & Bridges, K.. (2011). Effect of Syllabus Tone: Students’ Perceptions of Instructor and Course. Social Psychology of Education. 14. 319-330. 10.1007/s11218-011-9152-4.

- Perrine, R. M., Lisle, J., & Tucker, D. L. (1995). Effects of a syllabus offer of help, student age, and class size on college students’ willingness to seek support from faculty. Journal of Experimental Education, 64, 41–52.

- Wang, Haertal, G., & Walgberg, H. (1994). Educational resilience in inner-city. In M. Wang & G. E (Eds.), Educational resilience in inner-city America: Challenges and prospects (pp. 45–72). Hillsdale: Lawrence Erlbaunm Associates.

- Ye, W., Strietholt, R., & Blömeke, S. (2021). Academic resilience: underlying norms and validity of definitions. Educational Assessment, Evaluation and Accountability, 33(1), 169–202.

- Cutri, R.M., & Whiting, E.F. (2015). The emotional work of discomfort and vulnerability in multicultural teacher education. Teachers and Teaching, 21, 1010 – 1025.

- Indiana University Bloomington, “Write a Syllabus that Supports Student and Instructor Mental Health”: https://blogs.iu.edu/citl/2022/08/08/syllabus-for-mental-health/

- Lafever, M. (2017). Using the Medicine Wheel for Curriculum Design in Intercultural Communication: Rethinking Learning Outcomes. In Promoting Intercultural Communication Competencies in Higher Education (pp. 168–199). IGI Global.

- Tufts University, “Instructional Strategies That Support Student Well-being”: https://provost.tufts.edu/celt/guidance-for-supporting-student-mental-health/

- University of Pennsylvania, “Wellness Syllabus Language”: https://ctl.upenn.edu/resources/syllabus/student-wellness/

- University of Toronto Governing Policy on Academic Continuity (2012): https://governingcouncil.utoronto.ca/secretariat/policies/academic-continuity-university-toronto-policy-january-26-2012

- University of Toronto, “Resilient Course Design”: https://teaching.utoronto.ca/resources/resilient-course-design/

- Carleton College, “Resilient Pedagogy”: https://www.carleton.edu/ltc/resources/resilient-pedagogy/

- Bill Hart-Davidson, “Imagining a Resilient Pedagogy”: https://cal.msu.edu/news/imagining-a-resilient-pedagogy/

- University of Toronto EdTech Guide: https://teaching.utoronto.ca/educational-technology/

- University of Waterloo, “Resilient Course Design”: https://uwaterloo.ca/centre-for-teaching-excellence/teaching-resources/teaching-tips/planning-courses-and-assignments/course-design/resilient-course-design

- (Questions adapted from Linda Nilson, Teaching at Its Best, 2010, 40-41.)

- Colombia University, “Designing an Inclusive Syllabus”: https://ctl.columbia.edu/resources-and-technology/resources/designing-inclusive-syllabus/

- Harvard University, “5 Steps to Designing a Syllabus That Promotes Recall and Application”: https://hbsp.harvard.edu/inspiring-minds/5-steps-to-designing-a-syllabus-that-promotes-recall-and-application

- Toronto Metropolitan University, “Diversifying your course syllabus”: https://learn.library.torontomu.ca/c.php?g=725152&p=5193416

- University of Toronto, “Personalizing your Land Acknowledgement: Building from the Medicine Wheel”: https://teaching.utoronto.ca/wp-content/uploads/Land-Acknowledgments-Workshop-Tune-into-Teaching.pdf

- TATP Toolkit, “Writing Assessments,” https://tatp.utoronto.ca/teaching-toolkit/assessments/assessment-writing-guide/

- Queens University, “Making Assessment Criteria Clear to Students,” https://www.queensu.ca/teachingandlearning/modules/assessments/33_s4_03_why_is_clear_assessment_criteria_important.html

- Conestoga College, “Creating Clarity in Assignment Descriptions,” https://tlconestoga.ca/creating-clarity-in-assignment-descriptions/

- TATP Toolkit, “Scaffolding and Student Supports,” https://tatp.utoronto.ca/teaching-toolkit/supporting-students/cdg/assessment/scaffolding/

- TATP Toolkit, “Giving Feedback on Written Work,” https://tatp.utoronto.ca/teaching-toolkit/supporting-students/supporting-student-writing/giving-feedback/

- Shannon Obradovich, UBC, “Providing Effective Feedback on Writing Assignments,” https://sciencewritingresources.sites.olt.ubc.ca/files/2016/02/WACslides_feedbackworkshop_apr7_17.pdf

- Carnegie Mellon University, “Exam Wrappers,” https://www.cmu.edu/teaching/designteach/teach/examwrappers/

- Cornell University, Center for Teaching Innovation, “Self-Assessment,” https://teaching.cornell.edu/teaching-resources/assessment-evaluation/self-assessment

- Jeanna Towns, “A ‘Form’ of Flexibility: An Easy Way to Grant Extensions to Students,” https://blogs.oregonstate.edu/osuteaching/2022/04/25/a-form-of-flexibility-an-easy-way-to-grant-extensions-to-students/